In defense of John Montagu, creator of the sandwich & so much more.

A considerable literature on the origin of the sandwich has emerged in recent years. It is interesting on several fronts, if not only in terms of its intended purpose. The subject may appear trivial to casual readers, proof that food writers have too much time on their otherwise idle hands, but its treatment does mirror some fashionable historiographical techniques, none of them edifying.

Part of the problem may stem from ideology. Any number of journalists and historians appear to consider it their mission, or find it their source of jouissance, to deny powerful people from the past the influence that has been attributed to them. A corollary of this theme is the enthusiasm for undermining the legitimacy of elite figures. Dead white males not only are tedious to contemplate; worse, or better depending on your point of view, they also were posers, cads, self-dealing graspers and even legitimized murderers.

Writers sharing this outlook belong to a sort of Annales School run rabid. Ironically, they would be appalled to realize that they share a certain anachronistic tendency with the Victorian moralizers they no doubt despise.

Conventional wisdom considers John Montagu, Fourth Earl of Sandwich, a cheating husband and inveterate chancer when it considers him at all. The eclipse of his reputation began with indignant writers obsessed with religious rectitude during the nineteenth century. They imposed their own values on the behavior of people from a secular age, like Montagu, and found it wanting.

As N. A. M. Rodger notes with typical acuity, the fourth earl “has suffered the indignity of being forgotten as a man and remembered as a thing. When he is remembered, the ideas associated with his name are few and wrong.” (Rodger xii)

2. Complicated but accomplished and uncompromised.

In reality, as Rodger has demonstrated, Sandwich was a talented, tireless administrator with considerable charm and tact. He was adept at bringing otherwise intractable antagonists together in common cause. In 1748, for example, Montagu brokered the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle between Britain and France under difficult circumstances to great acclaim. He was thirty years old.

Sandwich would go on to serve a term as Postmaster General and two as Secretary of State. His association with the Admiralty, including three stints as First Lord, lasted eighteen years, from 1764 to 1782. Sandwich’s tenure spanned “some of the most important administrative, social and political developments in the history of the Royal Navy, in all of which he was intimately involved, and in many of which he himself was the prime mover.” (Rodger xiii)

His is a complicated story even by the standards of Enlightenment genius. Montagu was no moralist, and acknowledged a number of affairs, but that hardly looks transgressive, either by eighteenth century standards or in the circumstances of his marriage. “Wit, rake, poet and musician” to cite Rodger again,

“he also was a man whose private life was wounded by tragedy. He suffered the madness of his wife and the murder of his mistress, the deaths in turn of four sons, both his daughters-in-law and all but one of his grandchildren.” Rodger xiv)

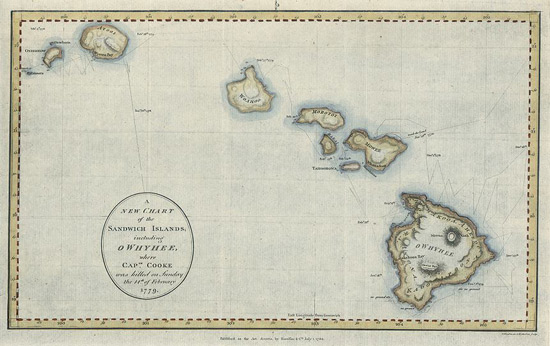

None of it stopped this polymath, “an amateur of history, astronomy and numismatics,” friend of Anson, Cook (who named the Sandwich Islands for him) and Garrick, champion of Handel, and active sportsman. His avocations included sailing, fishing, tennis, skittles (endearingly) and most of all cricket, a great passion. (Rodger xiv)

3. Bring me a sandwich and cut the cards.

All of which brings us to the sandwich. It is the minor invention of an accomplished man and a major focus of the frenzy to debunk.

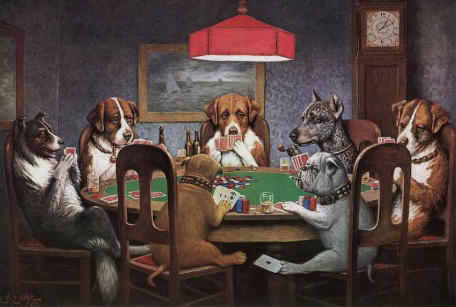

Conventional wisdom has credited Montagu with creating the sandwich during a card game. He was so inveterate a gambler (and “notorious profligate;” Katz 235), the story goes, that he did not want to interrupt play, so hit upon a way to eat while the game continued.

William Sitwell is typical, if atypically inelegant. In A History of Food in 100 Recipes, he describes Montagu as a “rake and a gambler, in the best eighteenth century tradition” who “was disinclined to leave the table for anything but a pee-break or to stretch his slick and slender breeches and stocking-covered legs” during a twenty-four hour “gaming session.” (Sitwell 141)

Another representative example of this narrative appears online under the headline “The Sandwich--a Word with Nefarious, Blasphemous, and Corrupt Origins.” One section heading trumpets the accusation that Montagu “was considered one of the most immoral men of his time.” (Wyz 1)

The text continues in the same vein: He was “immoral in both his private and public life, and gambling was just one of his lesser vices. He was the First Lord of the Admiralty, incompetent and very corrupt.” But wait, there is more. Sandwich was “the most universally disliked man in England” who was not only “anti-religious” but also “violently anti-democratic. He despised the general public and opposed any public figure who tried to get a better break for the common man” while boasting “that he specialized in seducing virgins.” (Wyz 1-2)

The article credits Montagu with creating the sandwich “during the very late hours one night in 1762” by recycling the conventional wisdom that he “was too busy gambling to stop for a meal even though he was hungry.” (Wyz 1)

4. I’ll have what they had.

Now, however, food writers and historians contort themselves attempting to prove that the earl did not invent the only thing he is remembered for. Nobody denies that Montagu ate sandwiches. Instead, writers scramble to show that in doing so he merely followed established practice.

Sitwell for one says “while the Fourth Earl of Sandwich may have given his name to this ingenious portable snack, he didn’t actually invent it.” (Sitwell 141)

“Sadly,” The Food Timeline states without offering any support for the lament, “the name of the real inventor of the sandwich (be it inventive cook or the creative consumer) was not recorded for posterity.” (foodtimeline.org 1)

The entry for “sandwiches” in The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink is typical, although more judicious than some in using a qualifier: “The fourth Earl of Sandwich was probably not the first person to place food between two pieces of bread and consume it by holding it in his hand.” (Smith 521)

A number of theories have been advanced to support the claim. In Sandwich: A Global History, Bee Wilson is thoughtful enough to put things right in terms of Montagu’s larger reputation. She has read Rodger and understands that the hoary calumnies about his excessive lust and gaming are unfair.

On the subject of the sandwich itself, however, Wilson proceeds from a dubious historical premise, shared by the majority of writers who address her subject. She argues that as a matter of ‘common sense’ something she considers so ‘obvious’ as a sandwich must have existed from time immemorial.

The appeal to ‘common sense’ is no substitute for facts, and in this case it is not at all clear that common sense tilts in the direction Wilson would take it. One writer, an H. D. Renner (eccentric outlier that he was), considers the sandwich an aberration. He is adamant that “according to all the rules of sciences governing nutrition the sandwich should never have been born.” Someone eating a sandwich sacrifices the “definite psychological reaction” that occurs when its filling is not obscured. “The sandwich is thus a poor substitute for a single slice of bread, spread with something one can both see and anticipate in advance.”

Anticipation delayed.

These “established facts of physiology and psychology” would, we may infer, explain why people chose not to create sandwiches before the modern economy forced the innovation upon them: “Their popularity owes much to the fact that the distances between home and work have increased enormously in recent times, and they can be so easily wrapped up and stowed away in a man’s pocket.” (Renner 223-24)

None of this is to endorse Renner’s syllogism, but it does illustrate the hazard of embarking on historical inquiry from a fixed assumption.

5. Forays into the Levant, the Low Countries and Larousse.

In her own quest for antecedents to Montagu’s creation, Wilson goes into considerable detail about the construction of the ‘Korech’ by rabbi Hillel the Elder sometime after 110 BC. The emphasis is odd, however, because as Wilson concedes, the Korech was not a sandwich at all, but rather an element of religious ritual, like the Catholic host, and it resembled something like a pita wrap. To cite Wilson herself, “Middle Eastern wraps have a lineage which is entirely separate from the European sandwich.” We might add that they lack a single name to unify them. (Wilson 26-30)

Despite Wilson’s characterization of his assertion, Simon Schama does not quite claim the first sandwich, a belegede broodje, for the Dutch in The Embarrassment of Riches. Schama may come close but will not go so far: The “famous belegede broodje boasts, he says, “greater antiquity than the sandwich,” which is not quite the same thing as saying it was a sandwich. (Schama 152)

Schama’s only reference for the boodje is from a travel book by John Ray published in 1673, which does not describe any such thing. Instead, Ray refers to what Schama describes as the “startling” and “strange habit in taverns of hung beef swinging from the rafters” which, Ray wrote, “they cut into slices and eat with bread and butter laying the slices upon the butter.” Possibly impairing his credibility, however, Ray also claims the Dutch ate a “Green cheese said to be colored with the juice of Sheep’s dung” the same way. (Schama 152) In any event the broodje neither appeared readymade at table for its diner nor sandwiched the beef or fecal cheese between slices of bread. No lid; no sandwich.

A (Dutch) invitation to sandwich making?

A (Dutch) invitation to sandwich making?

Wilson also would like to believe that the Dutch ate sandwiches during the seventeenth century, arguing that still lifes depicting food--cheese, bread and herring in one painting; ham, a roll and mustard in another; another roll and “a dish of tiny pink prawns” in a third--each amounts to an “invitation to sandwich-making.” (Wilson 33)

Dutch artists of the ‘golden age’ did not hesitate to depict any culinary item, but none of them produced the image of a sandwich. Neither does any other representational art form before the first appearance of the word in print. It would appear that nobody accepted the painterly invitation.

Undeterred by this lack of evidence, and offering none of its own, Larousse Gastronomique dismisses Montagu as the inventor of the sandwich, declaring that

“the concept itself is ancient. It has long been the custom in rural France to give farm labourers working in the fields meat for their meal enclosed in two slices of bread.” (Lang 935)

We should be forgiven for greeting this assertion with skepticism given its context. The French have a reflexive habit of taking credit for all things gastronomic but have no word, whether ancient or not, to describe the item under consideration other than the English ‘sandwich.’ Larousse itself is nothing if not Francocentric, conferring French names on dishes as obviously English as pease pudding (“pois cassés”) despite using the properly archaic term ‘pease’ in translation. It also is unreliable, dating the first appearance of the term sandwich to “the beginning of the nineteenth century” while repeating the dubious claim that Montagu ordered one so “he would not have to leave the gambling tables to eat.” (Lang 935)

The Encyclopedia of Food and Culture gives the fourth earl credit for introducing sandwiches to England but not for introducing them to the table more generally.

“In fact, Montague [sic] was not the inventor of the sandwich; rather, during his excursions in the eastern Mediterranean, he saw grilled pita breads and small canapés and sandwiches served by the Greeks and Turks during their mezes, and copied the concept for its obvious convenience.” (Katz 235-36)

In actual fact, grilled pita breads and canapés are not sandwiches, and nobody has found evidence of what we know as a sandwich among the Greeks or Turks of the time. Nor has anyone established that Montagu ‘saw’ or ‘copied’ Mediterranean ‘sandwiches.’ Lots of other young British grandees visited Greece and Turkey on the Grand Tour during the eighteenth century; if the convenience of the concept was so ‘obvious,’ why was it not copied by anybody else? Nobody, not even Montagu, commented on any such encounter with a sandwich in the Mediterranean.

They could be gyros.

6. Perhaps playwrights held the key… or not.

Enter Mark Morton. In a widely cited essay from Gastronomica he has argued that “[t]he sandwich appears simply to have been known as ‘bread and meat’ or ‘bread and cheese’” based on the appearance of the phrases in sixteenth and seventeenth century English plays. He places great store in his observation that ‘bread’ always precedes ‘meat’ or ‘cheese’ in these dramas, which indicates to him that the phrase was a term of art for ‘sandwich’ and that bread became the base for the protein. (Morton 6)

It is a specious argument, even putting on one side the observation that no image of a sandwich from the entire period exists.

People always say ‘wine and cheese’ instead of ‘cheese and wine.’ The same goes for ‘bread and circuses’ and a host of other conjunctive constructions. Nonetheless wine does not support cheese and a circus tent does not stand on bread. Nor does Morton’s argument address the fact that none of his texts refers to the essential second slice.

English is an inventive, prolix and promiscuous language. It therefore is difficult to believe that no word, let alone multiple words (bánh mi, burger, butty, caprisi, cheesesteak, croquet-madame, croquet-monsieur, dagwood, grinder, hero, hoagy, Italian, monte cristo, muffaletta, panini, po’ boy, sandwich, sarny, slider, sub, toastie, wedge…), existed for centuries to describe what would become so commonplace an item.

7. Damn the proof, full speed astern.

Given these difficulties of proof, each debunker attempts to buttress the argument by resort to incredulity and speculation. Morgan: “surely sandwiches existed long before John Montagu sat down to play cards. The earl could not have been the first person in England to hit upon the idea of placing a bit of meat between two pieces of bread.” (Morgan 6)

Wilson: “Common sense tells us that the thing itself… must be one of the oldest and most universal types of meal…; ” “So the earl gets credited with inventing something that must have been around for hundreds if not thousands of years;” “Workers did not need to give this snack a name;” “There is clearly something comically absurd in giving the sandwich a single point of origin, as if it were a light bulb or a spinning jenny;” “The earl cannot have been the first…;” “Many people must have combined cheese and bread [the reverse of Morton’s order!] into a ‘sandwich.’” (Wilson 16, 18, 19, 25, 31)

Anybody who does not suffer intellectual whiplash from the lavish repetition of ‘surely,’ ‘must be,’ ‘must have been,’ ‘clearly,’ ‘cannot have been’ and the like--coupled as it is with the absence of evidence--is not paying attention. And yet none of it causes Wilson a qualm. Why not? Because, she says, “this lack of evidence is not evidence that sandwiches were not eaten.” (Wilson 32)

Not a sailor.

Usually, however, an absence of evidence indicates evidence of absence. The argument beloved of Morton, Wilson and others is no different from insisting that Native Americans had the wheel, the sail and alcoholic drinks. These items seem commonplace enough today and would have been familiar to Europeans for well over a millennium by the time they first reached North America. Each was unknown to Native Americans.

Historical assumptions based on ‘common sense’ all too often prove unwarranted. Curry is timelessly Indian (No, it is a British creation.) and relies on ingredients like chiles, potatoes and tomatoes; they therefore must be indigenous to the subcontinent (They are not.).

By another analogy, a number of dishes now considered iconic do not in reality go back too far. English ‘classics’ like Beef Wellington, or steak and kidney pudding and pie, date only to the middle of the nineteenth century.

8. The evidence unfolds.

Aside from speculation, we do know a number of things about Sandwich himself and the origin of the culinary version of his title, or at least its first use in print. That occurred during 1762, and the writer was no less than Edward Gibbon. This is part of his journal entry from 24 November 1762:

“I dined at the Cocoa Tree…. That respectable body affords every evening a sight truly English. Twenty or thirty of the first men in the kingdom… supping at little tables… upon a bit of cold meat, or a sandwich.”

What have we here? An acute observer, distinguished historian, Member of Parliament, political commentator and bon vivant mingles with members of the British elite. They are eating sandwiches at a “respectable” establishment: The Cocoa Tree he describes is no den of iniquity. Gibbon is hardly a chronicler of the prosaic, and if he considered the practice ‘truly English’ we may take him at his word.

The practice was novel--eighteenth century trends started at the top of British society--and uniquely British. We would find nothing truly English, American or French about eating sandwiches today; the practice is universal. In 1762, however, it was not, so it attracted the attention of Gibbon.

He uses ‘sandwich’ as if familiar with the term, but also as if his reader may not be acquainted with it; another indication of novelty. The diners at the Cocoa Tree were not eating Korech, canapés or pita wraps. They have, however, filled their sandwiches with “cold meat,” another link to Montagu.

The next description of a sandwich, if not quite the word itself, occurs in 1765, and appears to have given rise to the myth of genesis at the gaming table. It is from a foreign travelogue, A Tour to London by one P. J. Grosley:

“A minister of state passed four and twenty hours at a public gaming-table, so absorpt in play that, during the whole time, he had no subsistence but a bit of beef, between two slices of toasted bread, which he eat without ever quitting the game. This new dish grew highly in vogue, during my residence in London: it was called by the name of the minister who invented it.” (Grosley 149)

Rodger, in whose scholarly league none of the other writers under consideration plays, is not persuaded by the tale:

“Grosley’s book is a piece of travel literature of a kind not unknown today; based on a brief visit to a country and no knowledge of the language, it combines some shrewd comments with many absurdities. There is no supporting evidence for this gossip, and it does not seem likely that it has any foundation, especially as it refers to 1765, when Sandwich was a Cabinet minister and very busy.” (Rodger 79)

9. Moderation in rakish things.

Brooks’s Club

Louis Jones, chronicler of Georgian clubland, insists that Montagu “gambled with caution and he drank without excess.” (Jones 92)

Rodger has examined contemporaneous correspondence and the records of Montagu’s clubs, which logged the in-house wagers of its members, including the amounts at stake, the winnings and losses. This documentation supports Jones’ claim that Sandwich was no reckless roller of the dice: His modest wagers were neither extravagant nor perverted during an era when gambling greased the wheels not only of elite society but also of the political deal. By the time Montagu became a member of Brooks’s in 1785, for example, “it had become the headquarters of the Parliamentary opposition.” (Rodger 78)

10. A moment of truth.

Rodger is unequivocal. “There is no doubt,” he believes, that Montagu “was the real author of the sandwich, in its original form using salt beef, of which he was very fond.” (Rodger 79) While Wilson does refer to the Roger biography, she does not divulge this passage from it, which would appear to punch a pretty big hole in her revisionist if equivocal analysis.

At the time Gibbon attributed the sandwich to him, Montagu was serving one of his stints as First Lord of the Admiralty and working very nearly around the clock. Rodger believes duty rather than gaming called the sandwich to Montagu’s mind:

“The alternative explanation is that he invented it to sustain himself at his desk, which seems plausible since we have ample evidence of the long hours he worked from an early start, in an age when dinner was the only substantial meal of the day, and the fashionable hour to dine was four o’clock.” (Rodger 79; see Jones 92)

Gibbon’s reference to consumption of sandwiches at the Cocoa Tree may have been the opening salvo. The first printed recipe for a sandwich, however, would await the publication of The Lady’s Assistant for Regulating and Supplying the Table in 1773 by Charlotte Mason.

By 1781 Burke had included the word in his correspondence but no recipe or description appeared in a North American publication until 1837, when the Philadelphia author Eliza Leslie described ham sandwiches, which she explains are “used at supper, or at luncheon.” (Rodger 343n87; Mariani 283; Leslie facsimile 123)

In terms of the sandwich Leslie was the scout in the United States; nobody else appears to mention the item until 1844, “but it was not until much later in the century, when soft white bread loaves became a staple of the American diet, that the sandwich became very popular and serviceable.” (Mariani 283)

Leslie herself professed to be a patriot, but although she did include a very few distinctly American recipes in the Directions for cookery in its Various Branches, her Directions appear overwhelmingly British, “many of them very close in wording to older English cookbooks.” (Szathmary vii) The sandwich, it appears, remained Gibbon’s “truly English” artifact for decades.

Given these markers, coupled with the absence of any earlier evidence in manuscript, painting or print, it is difficult to give credence to the debunkers who attempt to place the earliest sandwich in the Mideast, on the European continent or on a surface other than Montagu’s desk at the Admiralty.

It would appear to the judicious mind that Sandwich did after all invent the sandwich.

Sources:

Anon., Food Timeline FAQs: sandwiches, http://foodtimeline.org/foodsandwiches.html

Anon., “The Sandwich--a Word with Nefarious, Blasphemous, and Corrupt Origins,” www.wyzant.com/help/english/etymology/words-mod-sandwich (accessed 19 June 2013)

P. J. Grosley (tr. T. Nugent), A Tour to London; or New Observations on England and its Inhabitants vol. I (London 1772)

Louis C. Jones, The Clubs of the Georgian Rakes (New York 1942)

Soloman Katz (ed.), Encyclopedia of Food and Culture vol. 3 (New York 2003)

Jennifer Lang (ed.), Larousse Gastronomique (New York 1988)

Eliza Leslie, Directions for Cookery in its Various Branches (Philadelphia 1837)

John Mariani, Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink (New york 1999)

Charlotte Mason, The Lady’s Assistant for Regulating and Supplying the Table (London 1773)

Mark Morton, “Bread and Meat for God’s Sake,” Gastronomica vol. 4 no. 3 (Summer 2004)

H. D. Renner, The Origin of Food Habits (London 1944)

N. A. M. Rodger, The Insatiable Earl: A Life of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich (New York 1994)

Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches (Berkeley 1988)

William Sitwell, A History of Food in 100 Recipes (New York 2013)

Louis Szathmary, “Introduction and Suggested Recipes,” to Leslie, Directions for Cookery (Arno Press facsimile, New York 1973)

Bee Wilson, Sandwich: A Global History (London 2010)